How a tie can explain the adoption of innovation

We should start with the question: What is a tie? Many would argue that it is a piece of fabric used to complement a suit. This makes you look very slick and, let’s be honest, a little more confident as well. But in the face of the organization, it is an interesting garment. In this setting, it also has a normative meaning. A normative meaning entails that it created a norm, which was related to whether the person was perceived as legitimate or not.

Thus, the tie was worn every day by millions of employees like some kind of habit and gave legitimacy to those employees who wore it. In literature, this is called an institution, which is defined as “an established procedure … often represented as the constituent rules of society (the ‘rules of the game’)”[1].

So, why do we not wear a tie anymore?

What changed over time was that larger corporations started to introduce “Casual Fridays” into the workweek, where, in 1994, almost 50% of all large corporations included this in their practices [2]. What was intended as an idea to work on new ideas resulted in more than what was anticipated.

The silent killer of ties was the following: very legitimate employees, who had much respect, started to wear casual clothing on Friday. This resulted in other colleagues seeing that same person executing the same kind of work, on the same level, while also having legitimacy. What this caused was a break between the tie and its normative meaning. Employees who wore casual clothing could also be very legitimate now. The institution of the tie began to break down.

Over time, other employees began to pick up the idea of also coming to work without wearing a tie. They, namely, could be seen as legitimate just as they were with a tie. The introduction of Casual Friday is known in literature as institutional work, which is defined as “purposive actions of organizations to create, maintain, or disrupt institutions” [3].

Institutional work and diffusion of innovation

What we have just seen is how a purposive action destroyed the institution of the tie and created the institution of casual clothing. Another way to see this is that the support level for the tie decreased from high to low, while the support level for casual clothing (in that context) increased from low to high. If we now replace the words “tie” or “casual clothing” with “innovation,” you can get a sense of how a theory of innovation diffusion is created based on this.

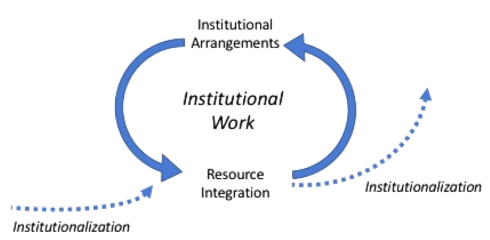

This new theory views institutional work as the motor of diffusion [4]. It argues that resource integration, such as Casual Friday, changes institutional arrangements. Institutional arrangements can be seen as the total mix of “normal” practices at a given time and place, where place can be on the micro (individual), meso (industry), or macro (society) scale. In this article, I focus on the industry level, where institutional arrangements determine the level of support for a given innovation.

How to make the motor of diffusion run well?

Just as every motor in our car needs gas, we must carefully select the right kind of gas at the gas station for each motor. If we put Euro-95 into a diesel engine, we will have trouble reaching 100 km/h.

So, what determines what kind of car we have? In literature, research has been conducted on characteristics that are important when performing institutional work. Because in this article I focus on the industry, we will look at what is important in an industry (the car) for institutional work to be performed.

Power distribution

Greenwood et al. [5] examined how power distribution within an industry is an important factor. They found that firms with significant power could shape changes within their professions. Hardy & Maguire [6] contributed to this by articulating that firms with less power can also contribute to change by forming alliances.

Resource distribution

Another crucial aspect of the industry is the distribution of resources among organizations. DiMaggio [7] pointed out that only those with sufficient resources could create new institutions. Furthermore, Colomy [8] articulated that resources could be used to negotiate and persuade other firms to support new practices.

Interconnectedness of organizations

The last example I give is regarding the interconnectedness of organizations in an industry. A higher level of interconnectedness can lead to more collective action, making it easier to perform institutional work [9].

What becomes clear from this overview is that many characteristics determine how institutional work can be performed within an industry. When firms want to change the support for an innovation, they must change what is perceived as normal in the industry to gain more support for that innovation. This requires institutional work, and if they do not examine what kind of car they have (power distribution, resource distribution, etc.), they might perform institutional work that does not fit that industry, like putting Euro-95 into your diesel. Good luck with that!

How to perform the right kind of institutional work?

In conclusion, after seeing that every industry is like a car with its own characteristics, organizations should consider this and ensure they perform the right kind of institutional work to gain support for their innovation, like putting the right kind of gas into their car.

Although we have seen that research exists on what characteristics are important to consider when performing institutional work, there is a lack of research on how organizations take these characteristics into account in their institutional work. If we can understand how these considerations work, we can (1) explain why specific types of innovations do not receive the support they need within an industry and (2) understand how to guide organizations in performing the right kind of institutional work, which could initiate the diffusion of innovation.

In the context of initiating the diffusion of PQC in the Dutch electricity management industry, this lens could provide new insights into how to get organizations moving toward it.

References

[1] Jepperson, R. L. (1991). Institutions, Institutional Effects, and Institutionalism. In The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 143–163).

[2] Don’t Thank the Boss for ‘Casual Friday’; Men’s Wear Angst, in: New York Times, July 26, 1994

[3] Lawrence, T. B., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutions and Institutional Work. In Sage Handbook of Organization Studies (Vol. 2, pp. 215–254).

[4] Vargo, S. L., Akaka, M. A., & Wieland, H. (2020). Rethinking the process of diffusion in innovation: A service-ecosystems and institutional perspective. Journal of Business Research, 116, 526–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JBUSRES.2020.01.038

[5] Greenwood, R., Suddaby, R., & Hinings, C. R. (2002). Theorizing change: The role of professional associations in the transformation of institutionalized fields. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069285

[6] Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2008). Institutional Entrepreneurship. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism (pp. 198–217). Sage.

[7] Dimaggio, P. J. (1988). Interest and agency in institutional theory. Institutional Patterns and Organizations, 3–32.

[8] Colomy, Paul. 1998. “Neofunctionalism and Neoinstitutionalism: Human Agency and Interest in Institutional Change.” Sociological Forum 13 (2): 265–300. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022193816858.

[9] Wijen, F., & Ansari, S. (2007). Overcoming Inaction through Collective Institutional Entrepreneurship: Insights from Regime Theory. Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1177/0170840607078115, 28(7), 1079–1100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607078115